The Old Stories Are Breaking

How do you cultivate hope when the civilization you inherited appears to be collapsing? When the news cycle is a conveyor belt of ecological ruin, political fracture, and technological alienation? When every inherited vision of the future—the gleaming chrome cities, the interstellar colonies, the frictionless digital utopias—has either failed to materialize or revealed itself as another mechanism of extraction?

The futuristic visions we grew up with were almost universally designed by and for the powerful. They imagined more of everything: more speed, more consumption, more control, more distance from the living world. Even the well-intentioned ones tended to assume that progress meant transcending nature rather than belonging to it.

Those stories are breaking. And in the cracks, something else is growing.

Solarpunk has been described as many things: a genre, an aesthetic, a political orientation. But perhaps the most honest description comes from those who practice it. Solarpunk is a mood, a whole vibe, a genre—and it is simultaneously all of these and none of them. It is less a fixed ideology than a shared orientation toward futures that feel lived-in, slow, and interdependent; built with dirt under your fingernails.

"Solarpunk is not escapist utopianism. It is the stubborn, practical insistence that better is possible—and that building it is the most meaningful work available to us."

This is a crucial distinction. Solarpunk does not promise perfection. It does not pretend that solar panels and community gardens will resolve centuries of colonialism, capitalism, and ecological destruction overnight. What it offers instead is a direction—a compass heading that says: this way leads toward life.

Rewilding How We Think With Language

Before we can build different futures, we need to think differently. And before we can think differently, we need different words.

The dominant language of industrial civilization encodes extraction at every level. We speak of "natural resources" as though rivers and forests exist to be converted into commodities. We call soil "dirt"—a word that means something worthless, something to be washed away. We describe economic activity with the metaphors of machines: inputs, outputs, efficiency, throughput. The living world becomes raw material; people become "human capital."

Notice what is missing from this vocabulary: reciprocity. Kinship. Regeneration. Belonging. Gratitude. These are not sentimental additions—they are load-bearing concepts that entire civilizations have been built upon. Indigenous languages around the world encode relationships with the living world that English literally cannot express. The Potawatomi word for a bay is a verb—it describes the water in the act of being a bay. The land is not a noun to be owned; it is a process to participate in.

Solarpunk begins here: with the rewilding of language. Reframing "collapse" as compost—the breaking down of old structures so that new life can feed on them. Reframing "waste" as resource in the wrong place. Reframing "weeds" as pioneer species doing the urgent work of soil repair that industrial agriculture has neglected.

This is not mere wordplay. Language shapes perception, and perception shapes action. When we change the words, we change what we can see. And when we can see differently, we can build differently.

Thinking Like a Forest

Ecological cognition—the practice of thinking in patterns borrowed from living systems—is perhaps the most powerful tool in the solarpunk repertoire. A forest does not think in straight lines. It does not optimize for a single output. It does not discard what it cannot immediately use.

A forest thinks in reciprocity: every organism gives and receives, and the health of any individual depends on the health of the whole. It thinks in circularity: waste from one process becomes food for another, and nothing is truly discarded. It thinks in redundancy: multiple species perform similar functions, so if one fails, the system continues. It thinks in succession: every disturbance creates conditions for the next stage of complexity.

"Collapse and renewal are the same process viewed from different temporal scales. What looks like destruction at the scale of a season looks like transformation at the scale of a century."

When we learn to think like a forest, the apparent contradictions of our moment begin to resolve. Economic systems are collapsing? Good—they were extractive, and what replaces them can be regenerative. Political institutions are failing? Of course—they were designed for a world that no longer exists, and what grows in their place can be more responsive, more local, more rooted.

This is not naivety. It is ecological realism. Systems that extract without returning always collapse. Systems that give and receive in balance persist for millennia. The question is not whether the extractive systems will end, but what we are ready to grow in their wake.

Art as Emotional Technology

Every civilization that has endured understood something that ours has largely forgotten: art is not decoration. Art is infrastructure. Civilizations perish not when their economies falter but when their art withers—when the shared stories, images, and sounds that bind people to each other and to the living world lose their power to move and to mean.

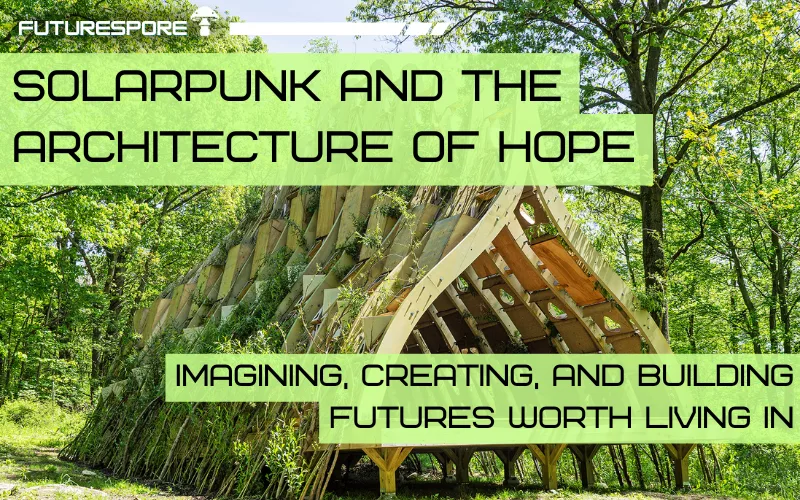

Solarpunk takes this seriously. Its visual culture—the overgrown skyscrapers, the moss-covered solar arrays, the community gardens cascading down terraced hillsides—is not merely aesthetic preference. It is emotional technology. These images rewire nervous systems trained on dystopia. They offer the visual cortex a different possibility: not sterile chrome control rooms, but living spaces where technology and nature interpenetrate. Not the cold vacuum of space colonization, but the warm, fungal embrace of a world that knows how to belong to itself.

When you see an illustration of a city where trees grow through buildings and solar panels pattern every roof like iridescent scales, something shifts in the body before the mind catches up. The shoulders drop. The breath deepens. Something says: I could live there. I want to live there. Maybe I can help build that.

That shift is not trivial. It is the beginning of agency. Art makes the abstract visceral, and visceral understanding is what moves people from knowing to doing. The overgrown skyscrapers do not just suggest a future—they suggest belonging. They say: even our mistakes can be reclaimed by life.

A Design Practice for the Disoriented

The systems we live inside were not designed to produce hope. They were designed to produce profit, and profit often requires despair. Despair sells pharmaceuticals. Despair sells entertainment. Despair sells the illusion that nothing can change, so you might as well keep buying.

Capitalist systems have become extraordinarily sophisticated at capturing attention and converting it into revenue. Your smartphone is a casino. Your news feed is a slot machine. The entire architecture of digital life is designed to keep you scrolling, reacting, consuming—never pausing long enough to imagine that something fundamentally different is possible.

Solarpunk is a design practice that relocates hope from abstraction into the hands. It is not hope as a feeling—it is hope as a verb. Hope as: I built a shared solar array with my neighbors. Hope as: we started a neighborhood repair café where nothing gets thrown away. Hope as: the makerspace on the corner teaches fourteen-year-olds to weld and wire and grow food. Hope as: the compost cooperative on our block diverts three tons of organic matter from the landfill every month and turns it into soil for the community garden.

"Hope is not something you find. It is something you build, with your hands, in the company of others, from materials that the dominant system considers worthless."

Each of these acts is small. None of them will, by itself, reverse climate change or dismantle industrial capitalism. But each of them creates a local proof of concept—a living demonstration that another way of organizing human life is not only possible but already happening. And these demonstrations are contagious. They spread through neighborhoods and networks, through stories and images, through the simple, radical visibility of people building lives that make sense.

Psychological Permaculture

Permaculture—the design science of working with natural patterns to create sustainable human habitats—is usually applied to land. But its principles extend to every system, including the ecology of the mind.

Just as a garden needs fallow periods to restore fertility, a mind needs silence. Just as a forest needs decomposition to feed new growth, a psyche needs space to grieve what has been lost before it can imagine what comes next. Just as a polyculture resists disease through diversity, a community resists despair through a diversity of voices, practices, and ways of knowing.

Psychological permaculture means protecting space for rest in a culture that valorizes relentless productivity. It means honoring grief as a form of love—you cannot mourn what you did not care for. It means understanding that burnout is not a personal failure but a systems failure: a sign that the human organism is being asked to produce without being allowed to restore.

In agricultural terms, a field that is never allowed to rest becomes sterile. The soil compacts. The microbial life dies. Yields decline even as inputs increase. The same is true of people. The same is true of movements. Rest periods are not indulgence—they are the precondition for sustained creativity. They prevent the sterility that comes from extraction without return.

Solarpunk understands this. It builds rest into its vision of the future. The solarpunk city has hammocks in the park, not just bike lanes. It has libraries where people sit for hours without being asked to buy anything. It has festivals that celebrate the turning of seasons, not product launches. It makes space for the slow, the contemplative, the apparently unproductive—because it knows that these are where the deepest regeneration happens.

Imagination as a Renewable Resource

We are told, implicitly and constantly, that imagination is a luxury. That serious people deal with reality as it is, not as it could be. That dreaming is for children and artists and people who have not yet learned how the world works.

This is, of course, exactly what any system that profits from the status quo would want you to believe. If you cannot imagine alternatives, you cannot build them. If the future looks like more of the same—only worse—then the rational response is to grab what you can and hold on tight. Scarcity of imagination produces scarcity of hope, which produces scarcity of action, which produces the very future we feared.

Solarpunk breaks this cycle by treating imagination as a renewable resource—something that grows with use, that feeds itself, that generates more than it consumes. Every food forest planted, every mutual aid network formed, every story told about a future worth living in adds to the commons of possibility. It becomes easier for the next person to imagine, because someone has already shown them it can be done.

Hope, in this framework, is not optimism. Optimism is a prediction: things will get better. Hope is a practice: I will work toward better, regardless of whether I can predict the outcome. Hope is the decision to plant a tree whose shade you may never sit in. Hope is the compost pile that takes months to become soil. Hope is the seed bank that preserves varieties for generations that do not yet exist.

"Collapse isn't the opposite of creation. It's what creation grows from. Every forest fire makes way for wildflowers. Every fallen tree becomes a nurse log. The old stories are breaking so that new ones can root in the cracks."

This is the architecture of hope: not a single grand structure, but a living, adaptive, self-repairing network of small acts, shared visions, and stubborn refusals to accept that the way things are is the way they must remain. It is built from the ground up, by people who have decided that the future is not something that happens to them but something they participate in creating.

The cracks in the old world are not just damage. They are openings. And what grows through them depends entirely on what we choose to plant.

Written by E. Silkweaver, founder of Futurespore.